KOBUDO – WEAPONRY

Okinawa’s Ancient Weapon Arts by Grandmaster George Alexander and edited by Ariza Shihan

A special thanks to Grandmaster Alexander for this informative and well documented piece of literature.

The weapons system of Okinawa martial arts, known today as Kobudo, meaning the way of ancient weapons, uses chiefly agricultural tools in the execution of its tactics. It was both practical and expedient. Kobudo, formerly referred to as Kobujutsu, was created out of a need for self preservation and its use dates back to antiquity in Okinawa. In fact, between the years 1100 and 1314, the Okinawans fought amongst themselves a great deal using all sorts of weapons. The use of staffs is particularly noted during this time. This was a time of civil strife and political unrest in Okinawa when many warring local chieftains sought to control various fiefs and villages.

The weapons system of Okinawa martial arts, known today as Kobudo, meaning the way of ancient weapons, uses chiefly agricultural tools in the execution of its tactics. It was both practical and expedient. Kobudo, formerly referred to as Kobujutsu, was created out of a need for self preservation and its use dates back to antiquity in Okinawa. In fact, between the years 1100 and 1314, the Okinawans fought amongst themselves a great deal using all sorts of weapons. The use of staffs is particularly noted during this time. This was a time of civil strife and political unrest in Okinawa when many warring local chieftains sought to control various fiefs and villages.

In addition, subsequent events in Okinawa’s history played a crucial role in the further development of Kobudo. In 1429 King Sho Hashi of the Central Kingdom united the three kingdoms of Okinawa by defeating the opposing lords of the Northern and Southern Kingdoms. Later, around 1480, King Sho Shin prohibited the private ownership and use of arms. He confiscated all weapons and placed a ban on the possession of any weapons to insure the safety of the Sho Dynasty. In 1609 Lord Shimazu of the Satsuma clan of southern Japan conquered all of the Ryukyu Islands. The practice of all martial arts and the possession of all weapons were banned. However, as it has been stated many times before, the Okinawans still practiced their martial arts in secrecy. These successive bans on the possession of weapons, which were meant to curtail martial arts practice, served to greatly increase its development. For over three hundred years Okinawa Kobudo was practiced secretly and handed down from one generation to the next with no written documents to record this period of development.

The Kobudo or weapons system of Okinawa uses the same stances and theory of movement as karate. Major tactics in Kobudo include the use of taisabaki or body shifting, trapping and hitting and simultaneous blocking and hitting. The practice of Kobudo is also a beneficial weight training regimen. It uses light weights, the weapons themselves, and a high number of repetitions. The five principle weapons of Okinawa Kobudo include the Bo, Sai, Nunchaku, Kama and Tonfa. Some other lesser known weapons are Ekku, Nitan Bo, Surichin, Tekko and Tenbei. Incidentally, in mainland Japan, Kobudo refers to the weapons of the Japanese samurai. These weapons include the sword (katana), halberd (naginata), spear (yari), bow and arrow (yumi and ya), etc. In order to avoid confusion, Okinawa’s weapons system is referred to as Ryukyu Kobudo or Okinawa Kobudo.

The Bo is one of the foremost traditional arms in Okinawa’s arsenal of Kobudo weapons. The Bo is a six foot wooden staff and is probably “the oldest weapon known to man other than a flung rock”. No doubt its use dates back to antiquity and there are many “classical” Okinawa Bo kata, numbering twenty five or more. Its agricultural use involves carrying loads such as a bundle of harvested rice or a water jug on either end. The Okinawa Bo is designed to be constructed so that it is tapered at either end. This aids in balance and manipulation of the weapon. The oldest existing Bo kata is Sakugawa no Kon. This form dates back to the mid-seventeen hundreds and was formulated by Tode Sakugawa (1733-1815). According to the Shinken Taira (1902-1970) Kobudo lineage, there are actually three forms or versions of the Sakugawa no Kon kata: Dai (major), Sho (minor) and Koryu (old style). Another Bo kata is Sunakake no Kon. This form is generic in that it is practiced widely and does not appear to be attributable to any one person, family style or village. The name of the kata means flipping sand and in fact its principle technique is to flip sand into the eyes of an opponent with the end of the Bo and then dispatch him with two quick blows. The Chikin Bo kata from Nishihara village dates back to the 1800s and features the reverse grip or left-handed use of the Bo. Perhaps the most advanced Bo kata is Chatan Yara no Kon. This kata dates back to Yara of Chatan Village who was active about the same time as Sakugawa. The kata is quite long and features an extension strike at the end.

and is probably “the oldest weapon known to man other than a flung rock”. No doubt its use dates back to antiquity and there are many “classical” Okinawa Bo kata, numbering twenty five or more. Its agricultural use involves carrying loads such as a bundle of harvested rice or a water jug on either end. The Okinawa Bo is designed to be constructed so that it is tapered at either end. This aids in balance and manipulation of the weapon. The oldest existing Bo kata is Sakugawa no Kon. This form dates back to the mid-seventeen hundreds and was formulated by Tode Sakugawa (1733-1815). According to the Shinken Taira (1902-1970) Kobudo lineage, there are actually three forms or versions of the Sakugawa no Kon kata: Dai (major), Sho (minor) and Koryu (old style). Another Bo kata is Sunakake no Kon. This form is generic in that it is practiced widely and does not appear to be attributable to any one person, family style or village. The name of the kata means flipping sand and in fact its principle technique is to flip sand into the eyes of an opponent with the end of the Bo and then dispatch him with two quick blows. The Chikin Bo kata from Nishihara village dates back to the 1800s and features the reverse grip or left-handed use of the Bo. Perhaps the most advanced Bo kata is Chatan Yara no Kon. This kata dates back to Yara of Chatan Village who was active about the same time as Sakugawa. The kata is quite long and features an extension strike at the end.

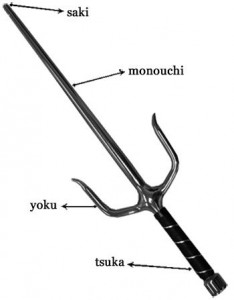

It was mentioned earlier that Okinawa’s Kobudo system uses chiefly agricultural implements. However, the Sai is not one of the Kobudo weapons derived from an agricultural source. The Sai is a metal trident-shaped truncheon whose military use has long been documented in Asia. The Sai used by the Okinawa samurai was a military weapon used in various other Asian cultures. Versions of the Sai appear in China, the Philippines and Indonesia. The Sai is a defensive weapon and is the symbol of the spirit of Okinawa Kobudo. The weapon is used in pairs to block and catch a sword or staff in its tines or quillions. Offensively, the weapon is used to strike an opponent with the shaft, spear with the tip or punch with the handle. Sometimes a third Sai was carried hidden in the belt at the small of the back. If one of the original Sai was lost or thrown a third one could be quickly withdrawn from the belt to replace the lost weapon. An interesting point to set straight here is that contrary to common belief the Sai was rarely used to defend against a sword. Okinawa Kobudo weapons were largely used against one another by Okinawa samurai. A primary example of this is the Sai versus the Bo.

It was mentioned earlier that Okinawa’s Kobudo system uses chiefly agricultural implements. However, the Sai is not one of the Kobudo weapons derived from an agricultural source. The Sai is a metal trident-shaped truncheon whose military use has long been documented in Asia. The Sai used by the Okinawa samurai was a military weapon used in various other Asian cultures. Versions of the Sai appear in China, the Philippines and Indonesia. The Sai is a defensive weapon and is the symbol of the spirit of Okinawa Kobudo. The weapon is used in pairs to block and catch a sword or staff in its tines or quillions. Offensively, the weapon is used to strike an opponent with the shaft, spear with the tip or punch with the handle. Sometimes a third Sai was carried hidden in the belt at the small of the back. If one of the original Sai was lost or thrown a third one could be quickly withdrawn from the belt to replace the lost weapon. An interesting point to set straight here is that contrary to common belief the Sai was rarely used to defend against a sword. Okinawa Kobudo weapons were largely used against one another by Okinawa samurai. A primary example of this is the Sai versus the Bo.

As with the Bo, the Sai has many “classical” kata. There are fifteen or more “classical” forms which are named after various villages or individuals who specialized in the weapon. Bushi Matsumura (1797-1889), one of Okinawa’s most famous warriors developed his own Sai kata called Matsumura no Sai. Another noteworthy kata is Chatan Yara no Sai. It contains many blocks, strikes, punches and flips with the weapon but it also has a unique defense. Towards the end of the kata it feigns a retreat or escape but then turns and immediately blocks and counters with a double strike. The kata also includes a hidden movement whereby a third sai is drawn from the belt and thrown into an opponent’s foot, pinning it to the ground. This was a Sai tactic used by many Okinawa masters of the weapon.

The Nunchaku (not nunchucks) is no doubt the most widely known weapon in Okinawa Kobudo. Some authors have suggested that the Nunchaku was derived from a horse bridle. Although I have no empirical evidence to submit, I know deep in my soul this is not the case. It is well documented that in European cultures an agricultural flail was the basis for a Nunchaku-like weapon which could reach over an enemies shield and strike him in the head. Perhaps an Okinawa horse bridle was later converted to a nunchaku but it had to have originally been fashioned from a flail. The weapon gets its power from centrifugal force by swinging it in a large arc while either blocking or striking an opponent. It can also be used in a grappling fashion to tie up an opponent’s attack and apply a crushing grip. There seems to be no “classical” kata with the weapon but rather informal kata and drills.

A weapon most certainly derived from agricultural sources is the Kama or razor-sharp sickles. It is ubiquitous throughout Asia and is used in the harvesting of rice. The weapon is used in pairs similar to the Sai. Fighting techniques and kata for the Kama are found in various villages throughout Okinawa. Kanegawa no Nichogama and Gushikawa no Kama are examples of these village traditions. One of the most well known kata is Toyama no Kama, supposedly named after Kanken Toyama’s (1887-1969) grandfather. Most kata uses the Kama feature punching, blocking and cutting using the reverse grip, and blocking and chopping using the forward grip. During the performance of kata the weapon is twisted so that it continuously cuts during offensive movements. Although it is a short range weapon its shinken (sharp) edge makes it formidable. There are modified versions of the Kama which have a cord or kusari attached to the handle so the weapon can be twirled or thrown and then retrieved. This is an attempt to increase the range of the weapon.

The Tonfa or Tuifa is yet another ingenious weapon devised from agricultural sources. It was originally a handle which was inserted into a millstone to turn it. The weapon is used in pairs to punch, block or twirl and strike making use of centrifugal force similar to the Nunchaku. Two grips with the weapon include honte mochi, natural or extended grip and gyakute mochi or reverse hand grip. The reverse grip positions the shaft of the Tonfa so that it is held along the forearm to facilitate blocking. These are the same grips used in the manipulation of the Sai. Kata for the weapon include Hamahiga no Tonfa from Hamahiga Island and Yaraguwa no Tonfa devised by Chatan Yara.

Some of the lesser known weapons of Okinawa Kobudo include the Ekku or boat oar. It is classified as a type of Bo because its manipulation and tactics are very similar to the Bo. Two “classical” kata for the Ekku include Akahachi no Ekku and Tsuken Sunakake no Ekku. Its tactics include flipping sand (suna) into the eyes of an opponent and then striking or cutting with the edge of the oar. The Ekku is sometimes used in odori, Okinawa folk dance. Nitan Bo, meaning two short sticks, is another weapon used in pairs. It is very similar to Filipino stick fighting and its kata emphasize flowing circular movements. The Surichin is a length of chain or rope with a weight on either end. It was worn as a belt and was used in a similar fashion as the Nunchaku, twirling to strike or ensnare and grapple. One method handed down is that a favorite Surichin tactic was to entangle an opponent’s legs. Another lesser known and esoteric weapon is the Tekko. These are a form of brass knuckles used in pairs and are more of a street fighting weapon as opposed to a pure Okinawa samurai traditional weapon. However, there is a formal kata known as Maezato no Tekko passed on by Bushi Maezato of Naha. Finally, another unusual weapon is the use of a shield and knife collectively known as Tenbei. In ancient times the shield was fashioned from a turtle shell or even a straw hat called zinkasa. The Matayoshi Kobudo tradition includes a Tenbei kata as part of its syllabus of forms.

It is the belief of the AJWBA that in Kobudo, as well as its empty-hand Goshinjutsu (improvised defense), sparring, or kumite, is highly regarded as the quintessential expression of the essence of the martial arts. “Kumite is the creative process by which one freely applies everything learned in basics and patterns (Gata) and uses it while under the pressure of combat. This is done by pitting one weapon against another in combat, making it totally spontaneous and putting one in touch with an ancient warrior spirit”. The AJWBA method of doing this is by matching one weapon against another in two-man prearranged sparring drills or kata. This is quite similar to modern kendo, Japanese sport swordsmanship. For example, there are a series of kata known as Kumi Bo (literally harmonizing Bo against Bo), a Sai Bo kumite kata, Tonfa Bo kumite, Kama Bo kumite and Jutte Bikken kumite. These kata are made up of a series of attacking and blocking movements extracted from the “classical” kata. Each series of blocks and counters is ended with one of the kata participants assuming a kamae or fighting posture before the next series of attacks and counters begins. This simulates the natural shift in the tide of battle which occurs in real combat. Since there is an inherent danger and risk of injury in free sparring with weapons, initially the drills are done in a totally prearranged manner to a cadence call or count in order to develop technique and timing. Eventually, in order to simulate Jiyu style or free sparring, there is a departure from the count. In Jiyu style the count is given only at the kamae-te points. The pattern of the sparring drill is then allowed to drift, as opposed to moving in a completely regimented mode. This is because the opponents stalk each other at the kamae-te points. They shift around looking for an opening and wait for the right psychological moment to attack. The idea is to alter the timing and the pattern of the kata at the kamae-te point (this is where it would normally occur in real combat) in order to get closer to actual free sparring.

It is the belief of the AJWBA that in Kobudo, as well as its empty-hand Goshinjutsu (improvised defense), sparring, or kumite, is highly regarded as the quintessential expression of the essence of the martial arts. “Kumite is the creative process by which one freely applies everything learned in basics and patterns (Gata) and uses it while under the pressure of combat. This is done by pitting one weapon against another in combat, making it totally spontaneous and putting one in touch with an ancient warrior spirit”. The AJWBA method of doing this is by matching one weapon against another in two-man prearranged sparring drills or kata. This is quite similar to modern kendo, Japanese sport swordsmanship. For example, there are a series of kata known as Kumi Bo (literally harmonizing Bo against Bo), a Sai Bo kumite kata, Tonfa Bo kumite, Kama Bo kumite and Jutte Bikken kumite. These kata are made up of a series of attacking and blocking movements extracted from the “classical” kata. Each series of blocks and counters is ended with one of the kata participants assuming a kamae or fighting posture before the next series of attacks and counters begins. This simulates the natural shift in the tide of battle which occurs in real combat. Since there is an inherent danger and risk of injury in free sparring with weapons, initially the drills are done in a totally prearranged manner to a cadence call or count in order to develop technique and timing. Eventually, in order to simulate Jiyu style or free sparring, there is a departure from the count. In Jiyu style the count is given only at the kamae-te points. The pattern of the sparring drill is then allowed to drift, as opposed to moving in a completely regimented mode. This is because the opponents stalk each other at the kamae-te points. They shift around looking for an opening and wait for the right psychological moment to attack. The idea is to alter the timing and the pattern of the kata at the kamae-te point (this is where it would normally occur in real combat) in order to get closer to actual free sparring.

This “Kumi” system uses mild (not full) contact with weapons (although it appears quite violent to the uninitiated, especially in the Kumi Bo and Sai Bo Kumite kata); it rather relies on a practitioner’s skill to focus and control his weapon during an attack and at the point of impact. Usually each attack is blocked so no contact is made to the body of an opponent with a weapon. However, the final blow or “coup de grace” in each kata is stopped or focused at a vital point just before impact. Other contemporary systems have been used for free sparring with weapons, which make use of protective gear and/or foam weapons. In Okinawa in the 1920s full contact Bo fighting tournaments where held in the central part of the island. The participants used headgear, gauntlets or gloves and kendo-like bamboo armor as well as sune ate (shin protectors similar to those used in naginata). Since many serious injuries were incurred by the fighters, the tournaments were discontinued. Perhaps the use of protective gear or foam weapons is the only safe way to spar with weapons in a tournament situation because of the danger involved, especially when one’s fighting spirit is aroused. But the “Kumi” system mentioned above is more in line with the traditional Okinawa spirit of Kobudo and its samurai legacy of weaponry as an art form.